How a former golfer and rock guitarist found cutting-edge work fighting crime in the data sphere.

BY CECILIA CAPUZZI SIMON, The New York Times, January 04, 2009 >>

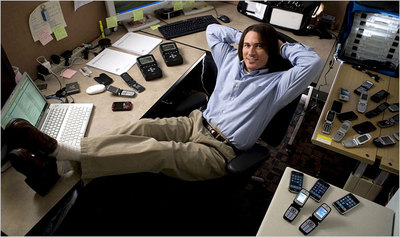

Rick Ayers doesn’t look much like the geek he says he has always been. A former golfer and rock guitarist, six feet tall, with a weight lifter’s build, long hair and a soul patch, Mr. Ayers, 37, stands out in the gray corridors of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the federal agency in suburban Washington that sets standards for the measurement sciences.

Mr. Ayers did not have his full-fledged geek credentials until age 32, when he earned a master’s in computer science at the University of Tulsa. The obsessive qualities that drove him at the tee and onstage have made him an expert in the use of handheld devices like cellphones, BlackBerries and P.D.A.’s in solving crimes. It is a booming specialty in the fast-growing field of digital forensics.

It is the rare criminal who doesn’t leave a digital trail, and the ubiquitous mobile phone has become a routine piece of evidence. But it is only useful if it is properly handled and its digital contents validated.

Cellphone sleuthing typically involves any of five jobs: extracting data from a device involved in a crime, be it text messages (even deleted ones), address book entries, to-do lists, pictures, audio and even the phone’s location when in use; examining that evidence; ensuring it is admissible in court; testifying as an expert witness; and as Mr. Ayers does, testing the “tools” — the software packages — that are used to recover the contents from a handheld device. Mr. Ayers also writes guidelines for handling electronic gear at crime scenes so evidence is not corrupted, and he presents his methods to computer scientists and law enforcement agencies worldwide.

Digital forensics was an unlikely choice, and one he doubts he could have handled as a 22-year-old who, he says, lacked the maturity to dedicate himself to the curriculum. Educators say that a solid grounding in computer science — how computers work, how to program, how to understand network intricacies — is essential to the field. Of course, not every adult bent on a career swerve into computer forensics takes a path as winding or intense as Mr. Ayers’s. Some only pursue certification, or are already intimate with a computer’s innards. Still, Mr. Ayers’s story is typical: it shows how a lifelong learner happens upon an unforeseen opportunity, and then everything changes.

Mr. Ayers thought he had his career mapped out at age 12, when he won 15 straight golf tournaments in Arkansas and was ranked his home state’s No. 1 player in his age group. Growing up at the edge of a golf course, he would hit 1,000 balls on a summer day, and he had his sights set on the P.G.A. But he withered under the pressure of national contention and left competition at 17. “It was a very difficult time,” he says.

He found solace in another obsession: the 1970s glam-rock band Kiss. He took up the guitar and joined a band as a student at Louisiana Tech University. As with golf, Mr. Ayers set a high professional goal: “full-blown rock star,” he says, laughing. He toured from Mississippi to Oregon with his group, Apache Rain, a pretty-boy hair band that liked to explode things on stage. But after two years, they were exhausted and barely breaking even.

Mr. Ayers moved to Tulsa and worked in telemarketing, then managed a small computer programming team. Without a computer science degree, he topped out in salary and job potential. He knew he needed to go back to school. “I understood how important it is to concentrate not on the cool things in life, but on the things that provide you with security,” he says. “I didn’t want to be Keith Richards at 60.”

He enrolled part time at the University of Tulsa with about 18 courses to go to complete a bachelor’s of science degree. The course load — programming languages, operating and data-based systems, computer security and forensics — gave him a broad understanding of computer science, he says. But it was a killer, too. He continued to work full time to support himself, spending free time studying or taking on freelance programming work; he got loans to cover tuition. The work-school combo became overwhelming. He had to rush between campus and his information technology job 30 miles away.

Sujeet Shenoi, a computer science professor, took notice and took Mr. Ayers under wing. He liked his quirky background, varied interests, outgoing personality and work ethic. He tapped him for graduate school and a federal scholarship known as Cyber Corps, aimed at grooming students for government jobs protecting electronic information from outside threats.

The award gave him a full ride, plus a stipend of $6,000 a semester, through two years of his master’s. He had to do a 10-week internship at a federal agency and agree to work for the government for two years after graduation. Otherwise, the curriculum is set by the school, and eligibility is institution-specific.

At Tulsa, aside from academic merit, Dr. Shenoi places a premium on personal traits: passion for computer science, patriotism, communication and leadership skills. Age, he says, does not matter. Of Tulsa’s 200 Cyber Corps graduates, more than 50 were over age 30 when enrolled; about 10 were over 50.

Mr. Ayers, who was 30 when he entered the program, felt intimidated at first by his young classmates. “These kids grew up with computers,” he says. “I grew up with golf and guitar.” But he learned to talk their language, surrounding himself with the smartest and inviting them over for pizza and study sessions. They, in turn, invited him to their parties and were eager to help. “They knew I worked hard,” Mr. Ayers says (his rock-band pedigree didn’t hurt, either).

If not for Cyber Corps, Mr. Ayers says, he probably wouldn’t have pursued a master’s. He was able to give up his job, and immersed himself in school for two years — no personal life, golf or guitar. There were demanding classes to get through, including five required certification courses. Mr. Ayers fulfilled the internship requirement at the National Institute of Standards and Technology. He did not expect to work in forensics. When he was recruited for a permanent post by the institute after graduation, his job was to study ways to make computer information more secure. But when asked if he had ideas for research, Mr. Ayers suggested retrieving evidence from P.D.A.’s — personal handheld devices were popular then.

It was a nascent field in 2003. Mr. Ayers was not the first to recognize the need to study this area, but he and a partner conducted some of the first research and wrote the first guidelines on extracting and handling data from handhelds. P.D.A.’s were just the tip of the iceberg. Soon the market would be flooded with cellphones that held personal data and had computing abilities. Today there are more than two billion mobile phones worldwide, twice the number of personal computers, and thousands of phone models. This year, more than two trillion text messages will be sent.

That’s a lot of potential evidence. And Mr. Ayers has his work cut out for him.

“After I get through testing C.D.M.A. phones,” he says, using tech speak for the network used by Verizon and other brands, “I go on to Smart phones, iPhones, Palm-based phones, Windows phones, BlackBerries, Google’s new phone. I’ll be doing this for another, I can’t tell you how many years.”

Career Switching? Elementary, My Dear Watson

COMPUTER forensics used to be the backwater of information technology, but the Internet and proliferation of cellphones opened new worlds of criminal mischief and bolstered work and study in the field. Here’s what you’ll want to know about what Gary Kessler, who teaches it at Champlain College in Vermont, calls “the most fun you can have with your clothes on.”

JOB PROSPECTS Employment numbers are not broken out for digital forensics, but it may be that rare employment category on the rise in this economy: the number of F.B.I. regional computer forensics labs grew from 3 in 2003 to 16 in 2008; investigations handled in that time more than quintupled. “Marketplace demand is higher than supply,” says Ravi Ganesan of the University of Texas, San Antonio. The biggest employers: government, corporate information-security departments, law enforcement agencies and law firms.Hot spots: Washington, New York, Dallas, Houston, Chicago and Los Angeles.

EXPECTED EARNINGS Salaries start at $50,000 for digital forensic examiners. Education, security clearances and fluency in another language can nudge earnings up to $100,000, and higher in the private sector, where senior managers can earn up to $200,000.

WHERE TO GET TRAINING More than 100 colleges and universities have courses in digital forensics either as majors or, mostly, concentrations. Among leaders in the field are the University of Tulsa, University of Texas at San Antonio, University of Central Florida, Johns Hopkins, Carnegie Mellon, Champlain and Purdue. A list of programs is at www.e-evidence.info/education.html.

EDUCATION SAMPLER Champlain offers a B.S. in computer and digital forensics completely online; or take just technical classes within the major for a 15- to 24-credit certificate. Purdue has a six-class specialization in its computer science master’s and, like Tulsa, a crime lab where students solve cases. Fairleigh Dickinson’s administrative science master’s includes a concentration that can be taken separately for certification. Classes are designed for working adults, held online, on-ground and on weekends at 50 locations in New Jersey, including at Trump Casino in Atlantic City. To see if the field is a good fit, try one of the one-day workshops.

Scholarships for Service

The Cyber Corps scholarship was established in 2000 to strengthen the cadre of professionals protecting the government information infrastructure. (Ironically, the kickoff was scheduled for Sept. 12, 2001, at the White House, an event that never happened.)

Officially the Federal Cyber Service’s Scholarship for Service (www.sfs.opm.gov), the grant covers tuition, books, room and board plus an $8,000-a-year stipend for up to the last two years of undergraduate study, or $12,000 a year for up to two years of graduate school.

In return, graduates work at a federal agency for one to two years.

Cyber Corps is sponsored by the National Science Foundation, with $110 million to date in Congressional funds, which are allocated annually.

Twenty-four institutions have been approved after a review of their security training curriculum, including Purdue, Johns Hopkins, Syracuse and Florida State University. So far 750 students have graduated, and 214 are currently on scholarship. Applications are made through participating schools, which determine individual eligibility requirements and select award recipients.