Living in the moment is tough, even for the idea's leading exponent. Just ask Jon Kabat-Zinn.

BY CECILIA CAPUZZI SIMON, The Washington Post, July 12, 2005 >>

Jon Kabat-Zinn is rushing through a breakfast of an egg-white omelet and green tea at the Omni Shoreham Hotel. He needs to be on time for the morning session at the Psychotherapy Networker Symposium. Yesterday he wowed the event's 3,600 mental health professionals with a keynote address titled after his new book, "Coming to Our Senses: Healing Ourselves and the World Through Mindfulness" (Hyperion, $24.95).

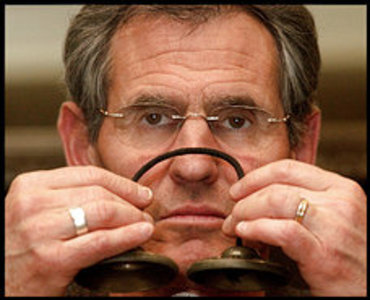

Graying, slight and fit, Kabat-Zinn looks younger than his 60 years and he seems more, well . . . human than his Zen-master reputation might suggest. The guru of mindfulness -- a way of living that urges people to find calm by connecting with the present moment -- is running several minutes late, having been waylaid by yet another conventioneer eager for his ear. Sitting straight- backed in the restaurant booth, he mentions the time, flags a waiter, spies acquaintances at another table and excuses himself to greet them.

Once back, he talks rapidly for the next half-hour -- mostly unprompted -- about the attention he's received at the symposium ("amazing"), the state of the world ("tortured"), the condition of our health ("dis-eased -- with a hyphen") and how mindfulness meditation can save us (through "a wise relationship with your sensory experience").

And then he is off: "Thank you for breakfast and your questions," he says. "What did you say your name is?"

It is reassuring to know that even "Mr. Mindfulness Incarnate," as Kabat-Zinn jokingly referred to himself during one workshop, is not immune to the distractions of a busy day. Mindful living may be good for our health, as Kabat-Zinn teaches and shows through his research. But living a mindful life in the 21st century is a challenge indeed. As his popularity illustrates, both professionals and regular folks who know their lives are overly hectic or emotionally out of whack are looking for ways to restore the balance.

Most realize, as Kabat-Zinn says, that the biological costs of ignoring stress are "huge," manifesting in cardiovascular and other systemic diseases and even, new research shows, in accelerated aging. And that's just the physical price. Unmanaged stress is also associated with anxiety, depression, eating disorders and other emotional illnesses.

"We are moving so fast, it is harder to know who we are," says Kabat-Zinn in a follow-up -- and more focused -- phone interview from his home in Lexington, Mass. "We're living great lives, but we're never there for them. . . . We have no time to linger or savor. We are starving for that."

The antidote, he says, is "paying attention, on purpose, . . . in a systematic way, in the present moment."

To many at the symposium, Kabat-Zinn is a kind of hero, whose writing and teaching has informed their work. Those who can't push their way into the auditorium where he's speaking watch from monitors in adjacent rooms.

"I can't see you," he announces into a bank of stage lights, "but I can feel you because of my extrasensory powers!" The audience laughs. Then he gets down to business, ringing a set of prayer chimes and leading a meditation.

"Tiny reverberations can have enormous implications," he says in a soothing voice. "Follow the sound of the tiny bells. Rest in the intrinsic wholeness of your own being. Rest in the experience of being here in this room, in the room of your own heart, in the moment, under thought, on the bank of the stream of thought."

The meditation goes on for five minutes, casting a spell that quietly draws in the audience so that all that's audible is the air pushing through the vents and the mid-morning gurgle of digesting Danish.

"We could pursue this for an hour," he says, concluding the meditation, "and it would be the best talk I'd ever give."

In his new book, Kabat-Zinn cites an intriguing theory by high- tech maverick Ray Kurzweil, who says that our internal sense of time is calibrated by new and unpredictable events that we perceive to be noteworthy. The more of these novel events in our lives, the slower time seems to pass.

Seeking to savor life, many of us fill our days, Kabat-Zinn says, "with as many novel and hopefully milestone experiences" as we can. We become addicted to this way of life, moving at light speed in search of new experiences, often turning to caffeine, alcohol, drugs or a new relationship, marriage, job or exotic vacation. But this frantic questing adds to our stress, and is responsible, in part, for what he calls America's "cultural attention deficit disorder."

Living mindfully -- "making more of your ordinary moments notable and noteworthy by taking note of them," he writes -- is another, usually healthier, way to slow down the sense of time passing. It also grounds us in the present moment, keeping us from living anticipatory lives, anxious about what's to come.

"Meditation is not about getting anywhere," Kabat-Zinn says at the opening of a meditation workshop, where more than 650 participants -- plus gate-crashers -- line the walls and take spots on the floor. "It's really hard for Americans to get that through their thick skulls. We're go-getters."

The workshop, like the keynote address, is a hubbub, a collective version of what Buddhists call "monkey mind," or our internal chaos, which meditation is meant to quiet and which, like all else in the "nowscape," as Kabat-Zinn calls the present moment, is ripe for mindful exploration. This includes the mind-state known as boredom, which he admits participants may be feeling.

"When you pay attention to boredom," he says, "it gets unbelievably interesting."

Kabat-Zinn first brought the Buddhist strain of meditation known as mindfulness to the mainstream of Western medicine 25 years ago. He developed a program called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and used it with patients at the stress reduction clinic he founded at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. It is now part of the school's Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, which he also established.

A molecular biologist with a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kabat-Zinn had a longstanding interest in Eastern healing traditions and meditation. He taught patients, most of whom suffered from chronic pain, how to use meditation to accept and ease their conditions. The eight-week course required participants to meditate 45 minutes a day.

It was highly experimental and very fringy, but patients reported remarkable clinical success. The claimed benefits included decreased pain and lowered blood pressure as well as a higher sense of well- being. Providers also took his course as a way to better treat and understand patients. Some 16,000 people have been through his clinic, and forms of MBSR are now used in more than 200 medical centers around the country to treat pain, cardiovascular disease and the effects of cancer therapy. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and its National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) have funded some research.

Kabat-Zinn knew that to be taken seriously he needed to conduct research showing the effectiveness of mindfulness in medical applications. Over the years, hundreds of such studies have been published. None has appeared in top-tier journals such as Science or the New England Journal of Medicine, but some have appeared in peer- reviewed journals devoted to pain, psychiatry, preventive medicine and alternative medicine. In the mental health field, mindfulness meditation is a centerpiece in the gold-standard treatment for borderline personality disorder (whose symptoms include problematic personal relationships and angry, impulsive behavior) and in a variation of cognitive therapy called mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

Kabat-Zinn's own research has turned up interesting applications and potential. In a 1998 study of psoriasis patients, those who listened to his meditations on tape during ultraviolet-light therapy healed four times faster than the control group. In another recent study, Kabat-Zinn and his collaborators showed that mindfulness meditation affects the prefrontal cortex of the brain, and boosts measurable immune response to a flu vaccine. Last year, NCCAM held its first symposium on the role of mindfulness in medicine.

Many remain skeptical about mindfulness and the quality of research published so far.

Most research into the technique is not randomized or controlled, meaning it does not reach gold-standard level, says Judith Beck, director of the Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research. (The institute, based in Bala Cynwyd, Pa., encourages high-quality studies on mental health interventions.) "That needs to be done," says Beck. "My clinical experience has been that having patients focus on their thoughts leads to more intense rumination. I've not studied it, that's just my experience.

"I encourage patients, especially with anxiety disorders, to explore different kinds of relaxation, including mindfulness. But I'm not trained in it. I don't do it with them."

Donald Klein, a psychiatrist and professor at Columbia University and director of the New York Psychiatric Institute, says that his review of mindfulness literature several years ago showed it to be "essentially anecdotal and therefore unconvincing." At this point, he says, he "couldn't recommend it."

Others say the field is too new to expect gold-standard validation.

Zindel Segal, one of the creators of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and a professor at the University of Toronto, says that alternative medicine generally is an "immature field with a lot of promise. The science has to be there, but you wouldn't expect a lot of definitive studies on its mechanisms yet.

"The clinical outcomes of mindfulness-based treatments are solid. It has established credibility in the field of physical disorders. We are now just opening the possibilities of treatment with mental health disorders. In five years, I don't know where we'll be. I hope we won't be crashing and burning."

Mindfulness' appeal is not "just about medicine," says Brian Berman, director of the Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Maryland. Berman is on his second NIH grant, this one to study the physical and emotional effect of mindfulness meditation on rheumatoid arthritis patients.

"People are looking for ways to help themselves and have control over their lives," he says. "We don't say 'stop the medication,' but we tell patients you can do other things to enhance the effects of standard care."

"How are you doing?" Kabat-Zinn asks workshop participants, rushing into the afternoon session. "Did you notice anything over lunch? You were there for lunch, weren't you?"

He is late because he spent his two-hour break -- without lunch or bathroom stop -- graciously signing books and taking time to talk with those who waited in a long line for a moment with him.

He leads the audience in a "caressing the air" exercise. They are like anchored kelp, he tells them, swaying and feeling the air. They fill the room with their waving arms and swaying bodies to the cadence of Kabat-Zinn's voice.

At the front of the room, Kabat-Zinn sits alone on a folding chair at the center of the platform, his eyes closed and his body still.

"The forest knows where you are," he tells the audience. "You must let it find you."